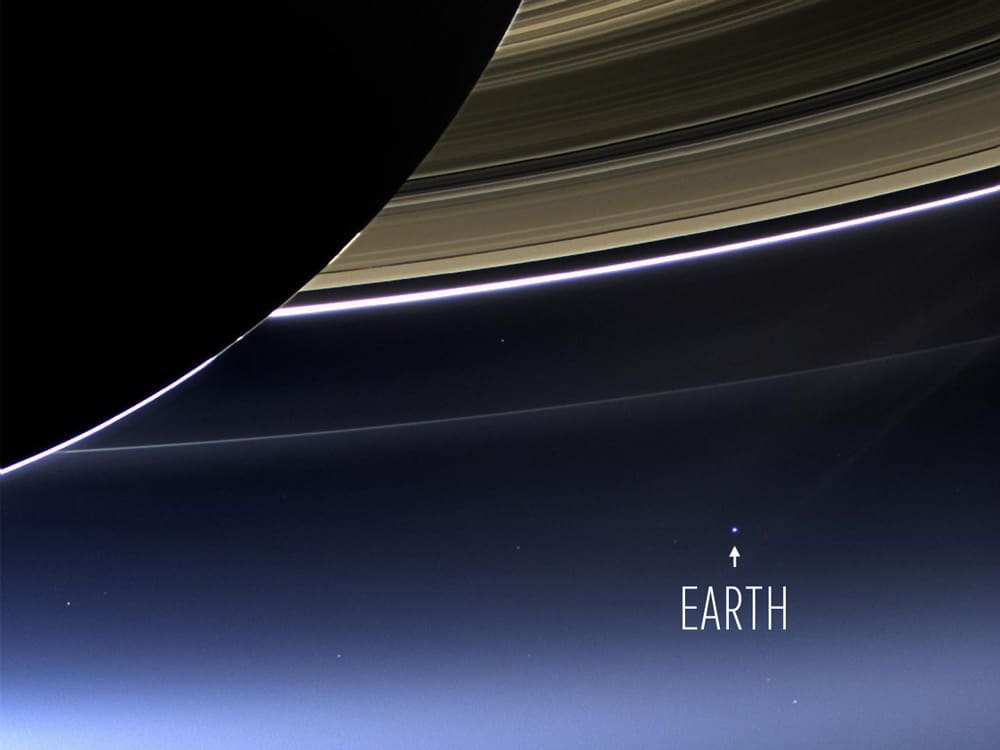

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has explored the Saturn system since 2004, re-writing our understanding of the giant planet, its rings, moons and magnetosphere. For 13 years the spacecraft’s incredible, truly otherworldly images have revealed the wonder of Saturn in surprising, often awe-inspiring ways. Cassini is planetary exploration at its finest, proving that to truly reveal the grandeur of a world, there is no substitute for actually going there.

Before Cassini, we had only brief glimpses of the discoveries awaiting us at Saturn. Pioneer 11 and Voyagers 1 and 2 conducted flybys decades ago, taking pictures, measurements and observations as they zoomed past. These missions shed new light on Saturn’s complicated ring system, discovered new moons and made the first measurements of Saturn’s magnetosphere. But these quick encounters didn’t allow time for more extensive scientific research.

Cassini changed all that. It began the first in-depth, up-close study of Saturn and its system of rings and moons in 2004. It became the first spacecraft to orbit Saturn, beginning a mission that yielded troves of new insights over more than a decade. The Saturnian system proved to be rich ground for exploration and discoveries, and Cassini’s science findings changed the course of future planetary exploration.

“We’re looking at a string of remarkable discoveries — about Saturn’s magnificent rings, its amazing moons, its dynamic magnetosphere and Titan’s surface and atmosphere,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini’s project scientist. “Some of the mission highlights so far include discovering that Titan has Earth-like processes and that the small moon Enceladus has a hot-spot at its southern pole, plus jets on the surface that spew out ice crystals, and liquid water beneath its surface.”

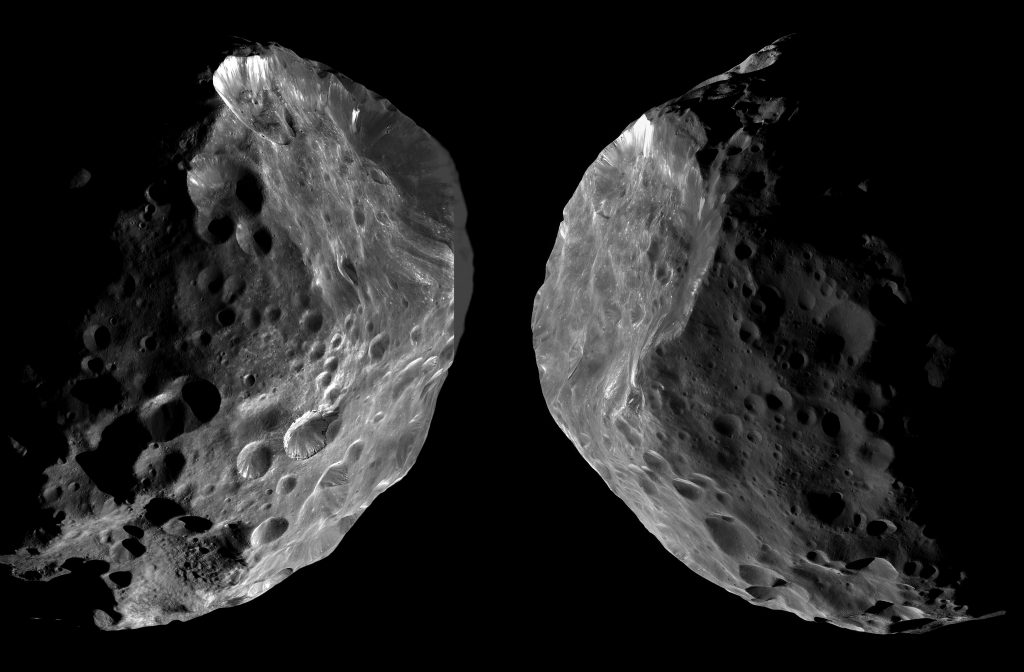

Some of the most surprising scientific findings have come from encounters with Saturn’s fascinating, dynamic moons.

Cassini’s observations of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, have given scientists a glimpse of what Earth might have been like before life evolved. They now believe Titan possesses many parallels to Earth, including lakes, rivers, channels, dunes, rain, clouds, mountains and possibly volcanoes.

The data from the Cassini spacecraft and the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe, which plunged through Titan’s dense, smoggy atmosphere to land on its surface in 2005, have generated hundreds of scientific articles and been the subject of special issues of the world’s most important scientific journals.

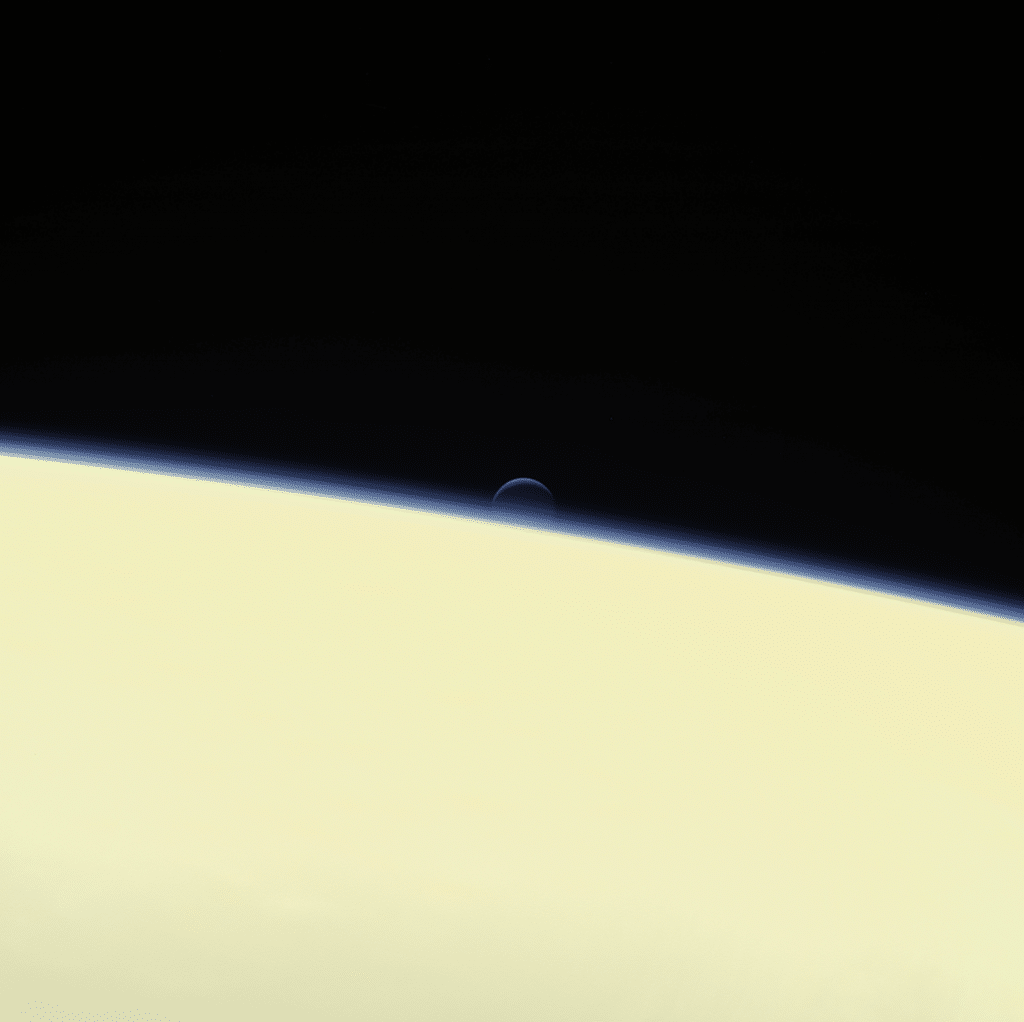

Enceladus, too, proved to be a rich source of discovery. The spray of icy particles from the surface jets forms a towering plume three times taller than the width of Enceladus itself. Cassini confirmed that the plume feeds particles into Saturn’s most expansive ring, the E ring. The spacecraft has come as close as 15 miles (25 kilometers) from the moon’s icy surface during its investigation, revealing the presence of a global subsurface ocean that might have conditions suitable for life.

Beginning in 2010, Cassini began a seven-year mission extension in which it completed many moon flybys while observing seasonal changes on Saturn and Titan. The plan for this phase of the mission was to expend all of the spacecraft’s propellant while exploring Saturn, ending with a plunge into the planet’s atmosphere.

In April 2017, Cassini was placed on an impact course that unfolded over five months of daring dives — a series of 22 orbits that each pass between the planet and its rings. Called the Grand Finale, this final phase of the mission has brought unparalleled observations of the planet and its rings from closer than ever before.

On Sept. 15, 2017, the spacecraft made its final approach to the giant planet Saturn. But this encounter was like no other. This time, Cassini dove into the planet’s atmosphere, sending science data for as long as its small thrusters could keep the spacecraft’s antenna pointed at Earth. Soon after, Cassini burned up and disintegrated like a meteor.

To its very end, Cassini was a mission of thrilling exploration. Launched on Oct. 15, 1997, the mission entered orbit around Saturn on June 30, 2004 (PDT), carrying the European Huygens probe. After its four-year prime mission, Cassini’s tour was extended twice. Its key discoveries have included the global ocean with indications of hydrothermal activity within Enceladus, and liquid methane seas on Titan.

And although the spacecraft is gone, its enormous collection of data about Saturn – the giant planet itself, its magnetosphere, rings and moons — will continue to yield new discoveries for decades.